(for best viewing of photos, click to enlarge and begin a slideshow)

|

"Self Portrait Along the Border Line Between Mexico and the United States,"

by Frida Kahlo, 1932 |

This, of course, is well-known through the work of Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, Frida Kahlo, José Clemente Orozco and

others from a certain era.

|

| (detail) "Production and Manufacture of Engine and Transmission" from the mural cycle "Detroit Industry," by Diego Rivera, 1932–33 |

|

(detail) The Dictatorship of Porfiro Díaz to the Revolution," by David Alfaro Siqueiros, 1957–1966. Museo Nacional de Historia

|

But

this tradition lives on throughout Oaxaca, as evidenced in my last blog post about street

art and graffiti in this city.

|

| Espacio Zapata Arte Popular, one of the print collectives in Oaxaca |

Currently connected with this are the print collectives and their resources for various creative enterprises. More about this below.

|

| Taller Siqueiros, another print collective. This is the outside sign |

The political spirit in Mexico perhaps stems from the Mexican Revolution (1910 – 1920), when workers revolted against greedy landowners,

condoned by long-time dictator Porfirio Díaz.

|

| Women revolting during the Revolution |

|

| The women's march! |

A lot happened during those 10 years, not least the death of up to

2,000,000 people (by some estimates) who were fighting (and another 300,000

people who died during the flu epidemic in 1918). As for the rulers, Francisco I. Madero

overthrew Díaz in 1911, was then ousted by counterrevolutionary Victoriano

Huerta in 1913; Huerta was exiled in 1914; Venustiano Carranza became the new

leader until he was shot in 1920; then Álvaro Obregón became president. Whew!

|

The hero of our story, Emiliano Zapata Salazar,

photographer unknown, [ca. 1911] |

The award-winning Hollywood film, Viva Zapata!, made in 1952 about revolutionary leaders

Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata Salazar, was etched into my memory (and

probably altered the course of my life) when I viewed it at a young age.

|

Marlon Brando playing the role of Zapata

in Viva Zapata!, 1952 |

This movie was written

by John Steinbeck (of Grapes of Wrath fame), directed by Elia

Kazan, and stared Marlon Brando and Anthony Quinn. It was hot! Thus was born

both my passion for black & white films of high drama and a revolutionary

spirit!

|

| poster for the Hollywood film, Viva Zapata!, 1952 |

Within a decade after the war, many Mexican painters had changed

their style and subject matter to represent their political alignment, and mural

painting "became the official art form."

|

| "Liberation of the Peon," by Diego Rivera, 1931 |

Although Mexico’s 1917 constitution called for a democratic government, it never really took hold until relatively recently. For most of the 20th century. the authoritarian Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) imposed a "patronage-based social order."

Despite its democratic disguise, "with all of its forms and trappings conveyed through elections and campaigns, it was largely a façade." This included manipulation of the voting system, and a "militarized rule prevented the authentic practice of democracy by often nullifying what should have been the effective powers of the electorate." Hmmm, sound familiar?

|

| "Trump Poison: Not Suitable for Human Consumption" |

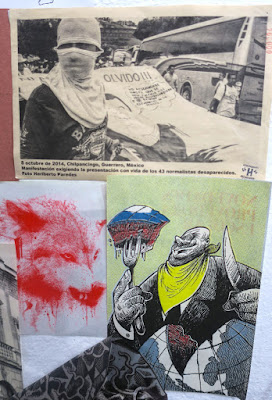

The impulse for artists in Mexico to reflect on social issues and injustices was recently highlighted after the 2014 disappearance of 43 students from the Ayotzinapa Rural Teachers' College in the state of Guerrero.

|

| Protester for the 43 missing students. Courtesy of the BBC |

A government-appointed panel found that the students, “who may well have been targeted for their left-wing activism, were brutally attacked and abducted by local police officers in league with members of the criminal organization known as Guerreros Unidos.”

|

"You Cannot Bury the Truth," by K.S. Helinska, 2015.

Designed in Poland |

Along with country-wide protests, art and posters were created around the world to commemorate the missing Mexican 43.

|

September 26, 2014," by Sahar Jalayer, 2015.

Designed in Iran.

|

A powerful figure in Oaxaca who led this movement is renowned

artist/activist Francisco Toledo, who has been instrumental in spearheading the revitalization of Oaxaca City, as well as nurturing and supporting printmakers, painters and writers in the city.

|

| The entrance to one of the print collectives |

|

| Getting ready to print |

|

| A student working at the Instituto de Artes Gráficas de Oaxaca |

|

"We want them alive:

Ayotzinapa resists" |

|

| "We will not forget, we will not forgive" |

|

| "Justice for Ayotzinapa!" |

|

"What happened to our corn?" This is in reference to the

genetic modification of corn in Mexico, ala Monsanto |

|

| The entrance to Siqueriros Centro Cultural |

|

| Sign in front of Siqueriros Centro Cultural |

|

| "Courageous Heros: To be a people makes a people" |

|

| The pun says "Revolubien" which translates "Revolt well" |

|

| "Live to be Free" |

|

| "We will defend the territory" |

|

| "For the mothers who cry over empty tombs for the children never return" |

|

| "We won't adapt to this system" |

|

"Monopolies, Capitalism, Fascism = The Internal Security Act"

This refers to a new act that makes it legal for government officials to search

a home or other place at any time without previous notice or warrant |

|

| "To protest is a right; to repress is a crime. No to the Internal Security Act" |

|

| "Without gold one lives, without water one dies" |

|

| "The Boss" |

Kent, Emerson. “The Mexican Revolution 1910-1920.” World History for the Relaxed Historian, www.emersonkent.com/wars_and_battles_in_history/mexican_revolution.htm.

Nydam, Anne E.G. “Mexican Political Art.” Black and White, 1 Jan. 1970, nydamprintsblackandwhite.blogspot.mx/2014/08/mexican-political-art.html.

“The Mexican Corrido.” Poemas Del Río Wang, 16 July 2008, riowang.blogspot.mx/2008/07/mexican-corrido.html.

“Viva Zapata!” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 28 Jan. 2018, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Viva_Zapata!